The following example shows what happens when coin-toss buying and selling a E-mini S&P 500 future contract that starts to drop in price. The trading account is worth 00, the broker fee is , the tick size (minimum increment or decrement allowed for this security) is 0.25 and each tick is worth .50. The profit is set to 4 ticks, the stop loss (a protection order that closes the trade in case the trade goes too much in the wrong direction) is also set to 4 ticks. The actual profit and stop loss are set equal to show that winning 50% of the times is not enough. Notice how, in order to close an open position the trader is actually going to send an opposite order (many trading platforms do this implicitly) of the same size, causing the actual “round turn” to apply the stated broker fee twice.

- Trade went allright and the profit got taken. The trader spent to open the position, gained 4 * .50 = and of course taking profit involved another in broker fees to close the position. The trader risked 4 * .50 = to earn – – = .

- The trade went south and a loss got taken. The trader spent to open the position, lost 4 * .50 = and of course closing the order at a loss still involved another in broker fees. The trader risked 4 * .50 = to earn - – – = -.

Therefore the trader by tossing a coin may earn on each win and loses on each loss. This means a net loss over time, therefore a coin toss is not enough. The trader has to gain an edge and achieve a bigger than 50% chance to win else he will eventually go bankrupt.

There could be made an argument about “letting only the profits run and cut the losses short” but besides complicating the example a lot, profits don’t run due to a random chance or gauging by eye or keeping the “close order trigger” warm. It takes a specific specialization that will be explained in another chapter. It may take months of practice before getting able to really let the profit run. Furthermore even the most skilled at letting profits run trader will have huge difficulties in case he does not have a sensible edge.

To make things worse, the example given is a fairly benign kind of market. Many markets, expecially those involving dealing desks could cost as much as 0 per contract (typical case being certain exotic currency pairs) to open a trade and then another 0 to close it. It gets fairly easy to see how a trader has to have a great edge to succeed at those markets. This assuming no requotes, no slippage and so on, those factors may tangibly worsen the resulting trader chances.

Last but not least, there’s price discovery, a truly powerful mechanic that makes markets move (apparently) erratically, in a way that makes mechanical (coin toss is one of them) approaches almost impossible to be profitable. At each time frame, price endlessy swings and bounces in reaction to the orders being activated, this causes all sorts of “shaking” and “bumping” that easily sends a less than competently managed open trade to the stop loss. Since price swings happen at all time frames, there is always a swing large enough that will manage to take unmanaged orders to stop loss as well.

Self optimizing, (mostly) self healing: due to the orders matching algorithms used by the exchanges, the markets tend to minimize their bid – ask spread. This yields tight and competitive pricing of the listed securities. Generally, the more the market participants and liquidity, the smaller the spreads. Markets may be taken with many strategies and even affected by them. However markets exhibit an uncanny nature to “learn” what’s used on them and to gradually make it less and less convenient. This is why every mechanical trading system tends to lose profitability over time. The more traders use it the more the trading system is “abused”, the less it becomes effective. The only two methods that so far have survived the decades are: price action trading and pure price trading (very loosely covered in this course). They survived because they basically follow the very motions of the market, which are very hard to disguise.

Self optimizing, (mostly) self healing: due to the orders matching algorithms used by the exchanges, the markets tend to minimize their bid – ask spread. This yields tight and competitive pricing of the listed securities. Generally, the more the market participants and liquidity, the smaller the spreads. Markets may be taken with many strategies and even affected by them. However markets exhibit an uncanny nature to “learn” what’s used on them and to gradually make it less and less convenient. This is why every mechanical trading system tends to lose profitability over time. The more traders use it the more the trading system is “abused”, the less it becomes effective. The only two methods that so far have survived the decades are: price action trading and pure price trading (very loosely covered in this course). They survived because they basically follow the very motions of the market, which are very hard to disguise.

- Supply meets demand: at the base of each market sits an asset. It may be a commodity, a simple item, a security, a contract, even a currency. This item is supplied and demanded by the market participants at a continuously varying rate. This item is therefore valued or priced in a correspondingly ever changing way. In a perfect markets and perfect competition theory, demand meets supply and price adapts within certain parameters and that’s it. Practical traders make a profit on what the perfect theories don’t cover or relegate to secondary importance.

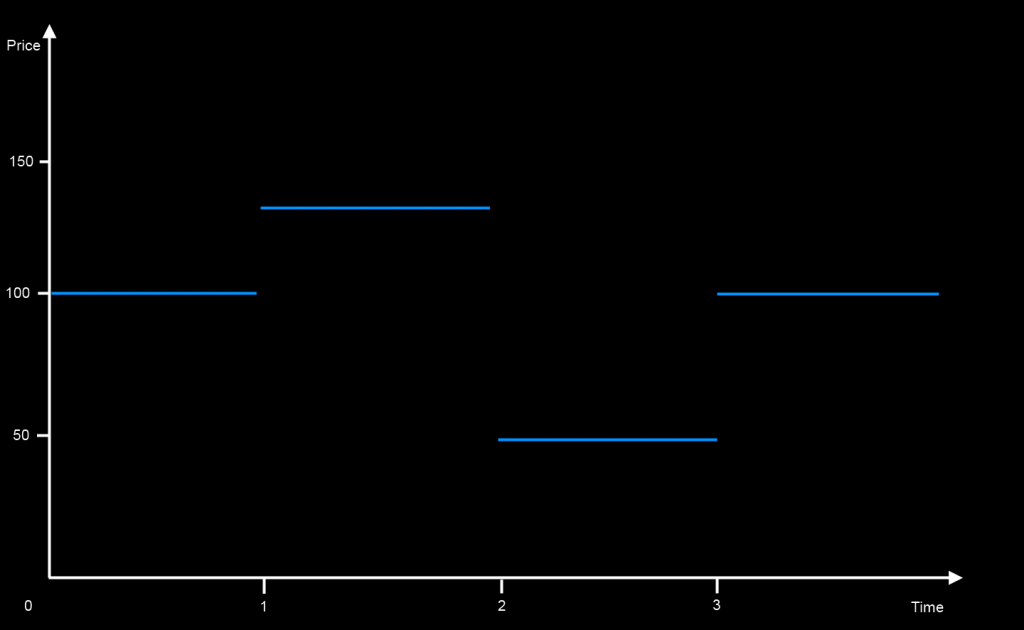

The following picture shows an hypothetical perfect market case where there only exists one asset producer and all the market participants are informed. Please refer to the Larry Harris book for the formal definitions of informed and uninformed players.

At T = 0 the supply is 100. At T = 1 it drops to 70, at T = 2 it rises to 150, at T = 3 it falls back to 100. The process is simplified a lot because this topic is not really relevant to practical trading operations.

Comments